Anachronox: Has Anyone Played this Buggy 2001 Masterpiece?

I’ve always had a soft spot for games that try to do too much, bite off way more than they can chew, and somehow still leave bite marks on the genre. Anachronox is that kind of game.

Released on PC in June 2001, it’s a sci-fi, film-noir, comedy-laced, JRPG-style adventure from Ion Storm Dallas, built on a heavily modified Quake II engine. It launched buggy, sold modestly, and came from a studio swirling in drama…yet it’s one of the most memorable RPGs I’ve ever played.

What the game is actually about (and why its cast is still memorable)

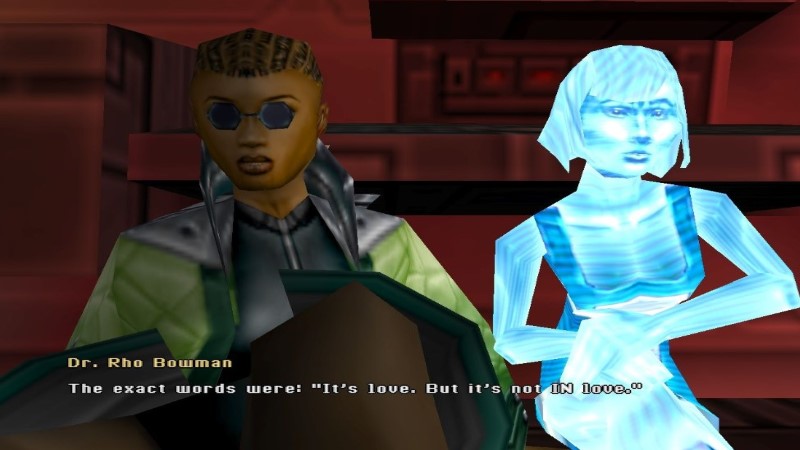

You play Sylvester “Sly Boots” Bucelli, a private eye on the scarred, seedy planet-city of Anachronox. He’s joined by a sarcastic childhood robot buddy (PAL-18), a grumpy scholar (Grumpos), a disgraced scientist (Dr. Rho Bowman), and (because Anachronox never met a big swing it didn’t like) an entire miniaturized planet called Democratus that somehow joins your party.

If that last bit made you grin, that’s the game in a nutshell: big ideas delivered with deadpan confidence. The plot ping-pongs from noir errands and mob feuds to galaxy-threatening mysteries tied to ancient “MysTech” artifacts, with sharp, funny dialogue and surprisingly heartfelt moments.

Mechanically, it wears its JRPG inspirations on its sleeve: turn-based battles, party skills for light puzzling, and hub-to-hub exploration but reimagined for a 3D PC space. The Quake II tech wasn’t just a renderer; Ion Storm hacked in cinematic camera work, expressive faces, and effects to make a “console-style” experience feel at home on a mouse and keyboard.

I’d argue Anachronox is still one of the cleanest translations of JRPG sensibilities to PC RPG culture in that era. Contemporary critics noticed the same thing, repeatedly comparing it to Final Fantasy while praising the story, humor, and character writing.

My take: the game’s tone is the secret sauce. It shifts from silly (Boots moonlighting as a dancer to make rent) to somber without whiplash, using humor to make the bigger cosmic turns land harder. When people say “great writing” in games, this is what they mean: voices you can hear in your head years later, and a world that lets both pathos and punchlines breathe.

The troubled road to release (and why the context matters)

Anachronox was in development for years, as it was originally targeted for 1998 but shipping in June 2001, and it lived inside the most public studio soap opera of its time. Ion Storm was founded by John Romero and Tom Hall, raised funding from Eidos, and split into Dallas (Daikatana, Dominion, Anachronox) and Austin (Deus Ex).

After Daikatana cratered, the Dallas studio became a punchline, and Anachronox had to find its footing under that cloud.

The team crunched brutally in 2000–2001 (12–16 hour days weren’t unusual), wrestling a shooter engine into a cinematic, turn-based RPG and running weekly “bug meetings” where new defects ballooned faster than the old ones could be squashed.

Even then, they got it out the door in late June 2001. Two weeks later, Eidos shuttered Ion Storm Dallas. The Anachronox crew stuck around unpaid to finish a patch. If you’ve ever wondered how “cult favorite with rough edges” happens…well, that’s how.

The buggy launch and the patchwork that followed

Day-one Anachronox was a paradox: critically praised but technically messy. GameSpot called it a “solid addition” and noted an early patch fixed “most” issues but highlighted Windows 2000 headaches; other reviewers loved the story but winced at the bugs.

Over the next few years, an official patch (1.01), then semi-official updates by programmer Joey Liaw, and finally an unofficial fan patch smoothed many of the worst problems: an early case study in community triage for a game that deserved better support than a closing studio could give.

My take: the roughness stung, but the writing and staging were so strong that I minded less than I should have. Once patched, the game’s charm shines through; the difference between a fascinating near-miss and a classic you want to evangelize. (Plenty of players and critics clearly felt that way, too).

Sales, reception, and the “best game no one played” problem

Commercially, Anachronox underperformed. By the end of 2001, North American sales were around 20,000 units, with some later tallies putting the early run closer to 40,000, which was tiny for a project this ambitious.

Yet reviews were broadly positive, and the game even popped up in PC Gamer’s Top 100 lists in later years. This is the weird duality of Anachronox: a game warmly received by those who found it, but drowned out by timing, minimal marketing, and studio turbulence.

How it helped (and quietly challenged) PC RPGs

Was Anachronox a commercial blueprint for PC RPGs? No. But in design terms, it was quietly influential:

- JRPG structure, PC comfort: It made a party-based, turn-based, story-first formula feel natural on PC without asking players to compromise on camera control, exploration, or interface. That sounds obvious now; it wasn’t in 2001.

- Cinematic staging in a shooter engine: Using Quake II to deliver elaborate cutscenes and camera language mattered. It showed that you could achieve theatrical storytelling without building bespoke tech from scratch, which was huge for mid-sized PC teams at the time. )

- Tone as a design pillar: The balance of melancholy sci-fi, noir grime, and straight-faced absurdity (again: a planet in your party) broadened what “serious” PC RPGs could feel like. Critics repeatedly singled out the humor and dialogue as defining features.

My take: Anachronox didn’t reshape the market, but it did expand the creative vocabulary of PC RPGs. When later games got bolder with cinematic cameras, authorial voice, or cross-pollination with console traditions, I always thought, “Yeah, Anachronox walked some of this road.”

The legacy: a cult classic that refused to vanish

If you only know one postscript, know this: Anachronox’s cutscenes were stitched into a feature-length film titled Anachronox: The Movie and it won top awards at the 2002 Machinima Film Festival. That wasn’t common back then; it validated how strong the game’s staging and writing were, even removed from the interactive bits.

On the studio side, Dallas closed days after launch, and both John Romero and Tom Hall parted ways at that time. What survived wasn’t a franchise (though Hall wanted a sequel) but a reputation; “the brilliant, broken Ion Storm RPG.” Over time, patches and fan love turned that reputation from “broken” to “beloved.” I still see it pop up in “underrated classics” lists, and honestly, it earns the slot.

So…should you play it today?

If you can live with 2001 production values and you’re okay applying community patches, yes, a thousand times yes. You’ll get:

- A sprawling, character-driven sci-fi road trip that alternates between hilarious, weird, and unexpectedly tender.

- Turn-based battles that aren’t the deepest ever made but serve the story and pacing well.

- A time capsule of PC-meets-JRPG design that still feels unique, not just “old.”

Personal verdict: Anachronox is messy, ambitious, and utterly singular. In a medium that often rewards safe bets, I’ll take a flawed masterpiece like this any day. It’s the textbook example of a game whose ideas outlived its sales chart, and that’s a legacy worth celebrating.